Stagecraft

Contents:

Legend: music genres in these notes:

- - Things specific to classical performances are shown ℭ𝄡→ like this ←𝄡ℭ.

- - Things specific to jazz and pop performances are shown ℥𝄞→ like this ←𝄞℥.

Back to contents-list

What is stagecraft?

Stagecraft is about how you move and look on stage. In other words, pretty much everything apart from the sounds you make. It's important for any musical performance, unless you're going to remain invisible to the audience before, throughout and after the performance!

.Back to contents-list

Who is this for?

Anyone going on stage needs good stagecraft. Some of the detail in these notes is aimed at someone leading a performance, and some is aimed at those who may not be leading but have to make independent decisions about quite a few things re. stagecraft.

The remainder, I hope, is relevant to a pretty wide range of people. For example, if you are a (non-solo) member of a large choir, you are unlikely to have to speak to the audience. And most of what you need to know about where/when/how to move (coming on/off stage, standing, sitting etc.), will be given to you - no decisions to make! You have to do it well, though!

And it might help to take a bit of time to remind yourself to balance your own needs with that of the audience and your co-performers, and why these things matter.

What is a stage anyway? If you are giving talk or a computer-based presentation/lecture, for example: is any of this applicable to you? I would say it is: not of course the stuff about amps and music stands. But if you have an audience, there are principles that need looking after...

.Back to contents-list

Summary of essentials

All this advice is based mainly on nothing more complicated than being nice to other people! Of course there are some more detailed things to consider, but in essence:

- • You're there for the audience, and you must show them courtesy and respect.

- • Performance is a two-way street: if they show their appreciation of you, it's courteous to acknowledge it. They should of course show you respect as well: applause is part of that process.

This means:

- • Be polite in all your dealings with people, whoever they be:

- ◦ your audience

- ◦ fellow performers

- ◦ concert organisers

- ◦ technicians, piano tuners, etc.

- ◦ cleaners

- ◦ porters

- ◦ etc.!!

- • Take good care of instruments, equipment, etc.

- ◦ Never put water or anything else on the piano!!

- • Be timely! If you don't plan and act ahead, you will probably make life awkward for someone.

- • Stagecraft needs frequent practice on and off stage! This is a courtesy to your audience, but it will also help you a lot.

- • Think positively! (This will help with everything!)

- • Stagecraft is a fundamental essential of any performance!

- ◦ Be, and look, confident

- ◦ Make eye contact with the audience

- ◦ Keep in touch with your co-performers, and make sure the audience know you are. These contacts need to be subtle and unobtrusive, of course.

- ◦ Breathing and posture are important for all musicians to get right (off stage as well as on...).

- ◦ The overall architecture of your performance, as well as the details, will have implications for your stagecraft.

Back to contents-list

General advice

Don't leave this to chance. Stagecraft is as much part of the performance as the notes you play and the words you sing, and can have a huge impact on how successful you are on stage. Stagecraft is not rocket science, but like any other skill, it needs frequent practice.

If for example you allocated just a couple of minutes each day to it, that might well be enough, but without that frequent practice it won't become second nature: looking, and feeling, confident and comfortable with how you appear and move on stage will put you and your audience in a good frame of mind, but it won't happen if you have to think about it too much: on stage, there isn't time for that!

Please don't think that this is something that only applies to ℭ𝄡→ classical concerts. ←𝄡ℭ!! Yes, typically, specific stagecraft-expectations of ℭ𝄡→ classical performers are different from, and perhaps more complex than ←𝄡ℭthose of ℥𝄞→ jazz and popular-music performers, for whom there are perhaps fewer conventions to observe as such, but it is no less important for you. ←𝄞℥

You can practice most things away from the venue. Taking a bow, for example - a simple act for sure, but one that needs to look graceful, perhaps occasionally more energetic, depending on your character and the character of your repertoire. You need to be fully in control of the timing of it.

This you can rehearse in a practice room, for example: practice performing the final few bars (or hearing them in your head, if it's the accompaniment); practice your body language as the end approaches as well - and the very ending - is it energetic with a physical gesture from you to match, or is it calm, or disturbed but intensely quiet, in which case you can hold the moment - don't move for perhaps several seconds, even up to quarter or half a minute in exceptional cases. You need to be comfortable with all this and that means, like any other skill, doing it lots of times before the real thing.

There is, however, no complete substitute for a real stage. So perform as often as you reasonably can, without overstretching yourself.

If you are asked to speak to the audience, research, plan and practice what you are going to say. Again, this is something you can do anywhere.

.Back to contents-list

Setting the stage

- - Contact all your co-performers well in advance to find out what they need.

- - Always be courteous to everyone at the venue!

- - Contact the venue plenty of time in advance.

- - Answer e-mails etc.:

- • Courteously

- • Promptly

- • Concisely

Back to contents-list

Planning the stage set

Work out your stage arrangement first so that it works aurally: within any constraints that makes, try to make it work visually as well. So think about:

- - How each instrumentalist or singer on stage will project

- - What balance you want between them

- - Any visual communication necessary between performers during the performance

- - Making performers as visible to the audience as reasonably possible:

- • Try not to have anyone stand/sit directly in front of anyone else if possible, but bear in mind that sometimes it's not possible to avoid someone being partly blocked (visually) from at least one part of the hall. This gets more difficult with:

- ◦ More performers

- ◦ A narrower, deeper, stage

- ◦ Flat (as opposed to raked) audience seating

- • The angle a performer is to the audience can be important visually as well as for projection of sound: For example, in duo performance, players turned towards each other might add to an intimate feel of the music (if that's appropriate), but too much of that can make an audience feel a bit excluded!

- - The route performers will take to get on and off stage. (Please see notes on coming on and off the stage, and some examples of moving around the stage ).

Back to contents-list

Getting it done

(1) If you are responsible for setting the stage,

- - try to procure help in advance if you need to move:

- • Many items (chairs, music stands, etc.) or

- • Heavy items

- • Bulky or awkwardly-shaped items

- - Make sure you've done some manual-handling training!

˜ ˜ or ˜ ˜

(2) If someone else is setting the stage for you, make sure they have clear written instructions, preferably with stage diagrams.

Whether (1) you are doing it yourself, or (2) passing on instructions to someone else: Make sure you have dealt with all of these that might be needed (items marked ♫ !❢ are always needed!):

- ◦ Positions on stage of seats, piano stools, percussion thrones, etc.

- ◦ Position of piano / keyboard instruments

- ◦ Music stands - positions and type

- ◦ Flat stands for e.g. mallets, mutes. These need to be damped, i.e. not make a noise when a mute or whatever is placed on them. (If possible, use a mallet stand)

- ◦ Power points on-stage for any amplifiers, etc.

- ◦ Positions of amplifiers etc.

- ◦ Power points/room off-stage (probably) for recording equipment

- ◦ Water on stage (preferably in glasses, on a table)

- ◦ Lighting

- ◦ All fire exits must remain clear ♫ !❢

- ◦ Keep clear paths for each performer to get on and off stage. ♫ !❢

- ◦ All loose cables on any bit of floor which might be crossed by anyone must be covered by a rubber mat. ♫ !❢

Back to contents-list

Tuning

.Back to contents-list

Pitfalls and checks

Be careful:

- • not to confuse your pitch with sympathetic resonance from the piano, or with any resonance from the room you're in (i.e. comparing like with like).

- • to make sure you know whether you're comparing fundamentals or upper partials. The ratios of the upper partials on the piano might not be the same as they are on your instrument. (This is more of a problem for wind instruments than strings).

- ◦ focussing on the fundamental is usually a good move, but if the upper partials are a long way out, and quite prominent, then you might want to compromise between them and the fundamental.

If you're a wind or brass player:

- ◦ Try to tune a wide range of high/low pitches, and different dynamics;

- ◦ Check the tuning of each valve (brass);

- ◦ Check tuning with the mute as well if necessary.

Back to contents-list

Initial tuning offstage instead of onstage

It can be very effective to start a recital without tuning on stage - if you want a more immediate and concentrated start to the recital, for example. Or a particularly dramatic entrance - this isn't always the sole preserve of singers!

But: never risk playing out-of-tune! Don't skip the on-stage initial tuning unless you can be sure of all of:

- ◦ You know exactly what pitch the piano is at (e.g. A=440)

- ◦ You can know exactly what that pitch should sound like, e.g. if you have an electronic tuner, can you adjust it to the right pitch

- ◦ Having tuned it, you can be sure that you can keep it in pitch till you arrive on stage

For example, suppose you have a tuning fork, or an electronic tuner set that can't be adjusted easily, set to C=256Hz or A=440Hz, If the piano is a bit sharp, e.g. A=443Hz, then you'll be out.

Or even if you can tune it OK, if you have for example to wait in the wings and can't play or blow air through your instrument, and the temperature is very different, it will go out by the time you get on stage.

On occasions when you still have access to the stage just a very few minutes before the performance starts, it can be possible to skip the on-stage tuning. .Back to contents-list

Tuning offstage anyway

By all means tune offstage anyway if you conveniently can: again, you need to know what pitch you're going to be working to onstage, but even if you don't know this exactly, getting the instrument as close as you can, and as self-consistent as possible, is obviously a good idea.

.Back to contents-list

Tuning during a recital

Again, never risk playing out-of-tune! It's much better to tune between pieces, or even between movements of pieces, than:

- ◦ straining to play in tune, e.g. by having to

- • lip up all the time

- • compromise on dynamics

- • avoiding open strings when they are appropriate

- • or even playing some notes up or down the octave!

Back to contents-list

The performance (summary)

- ◦ In all matters, consider your audience and be courteous to them!

- ◦ Dress appropriately!

- ◦ Note any instructions you are given about when/where to go on stage

- ◦ Making your entrance as a performer. (Please see here for more details)

- ◦ Smile and look relaxed

- ◦ Acknowledge the applause, (together with your co-performers), as soon as reasonably possible.

- • ℭ𝄡→ classical concerts: bow, or at least a definite nod of the head ←𝄡ℭ

- • ℥𝄞→ jazz/pop concerts: you can be more informal, but some definite signal of thanks to the audience ←𝄞℥

- ◦ When all your co-performers are in position:

- ◦ [if appropriate: Introduce the piece(s): speak clearly and not too fast! (Please see here for more details)

- ◦ Start the music - see details below.

- ◦ Craft the ending of each piece - character and body language.

- ◦ Smile when the audience applaud. At the end (final applause), either get your co-performers up and then all take a bow together, or take your own, then get them up for a group bow.

- ◦ Go off, again looking calm and confident. (A smile is a good thing here, too). Don't rush, but don't hang about.

- ◦ You are a performer until you are completely out of sight of the audience.

- ◦ Where possible, and depending on the how formal the occasion is, don't go into the audience area until well after the applause has finished. Often this isn't physically possible anyway, but when the stage is on the same level as the audience area, e.g. it's not raised up, etc., and where the stage-exit is at or near the front rather than the back, this can be a bit easy to do accidentally. Doing so can take the edge of the end of a formal performance.

Back to contents-list

Coming on to the stage

There are some examples later on in these notes. Here's the sequence of events etc.:

- • You'll by now know the stage layout, and where on stage you will stop to acknowledge the applause (and to speak, if you are speaking. And where any co-performers will stop similarly. Try to make sure that spot is somewhere which:

- • is reasonably central on stage, if possible

- • but within that, minimises how far you and your co-performers have to walk to get there. (This is a courtesy to the audience, so they don't have to "applaud you in" for too long).

- • is probably in front of, rather than behind, your music stand (if you have one)

- • You'll also know your route to that spot: ideally this should be:

- • as direct as reasonably possible

- • as unhindered by stage furniture as reasonably possible

- • allowing you and any co-performers to be visible, i.e. where there's a choice and it won't add much to the time involved, go in front of chairs/stands/etc., rather than behind them.

- • Just before you start walking on, glance at the stage, for real if you can, or on a CCTV if you have one offstage, or in your mind's eye: remind yourself where you're aiming for, i.e. where you'll bow (and speak from if you're going to speak before the piece starts)

Then: normally:

- • Smile! Look relaxed and confident, and engaged with the audience.

- • Don't rush, but don't dally either: if you saunter too slowly it can look a bit haughty.

- • Acknowledge the applause as soon as you get to your spot and your co-performers are in theirs. Usually this means:

- • Bow (or curtsey if you like), smilingly and naturally

- • Or, if it's a less formal occasion, you can nod in such a way that makes it clear that you're thanking them for the applause, and are about to speak, or to get on with with performance

- • Give yourself time to settle, get your posture and breathing just how you want it, before you start.

Unless you're planning on a particularly dramatic start... In which case you might not have time for the last of the above steps, for example. This will take extra practice!

Even the normal acknowledgement of the applause can be skipped if you are performing an operatic aria on a concert stage, but totally in character, including in the way you come on stage. It must be totally in character for this to work, i.e. not be in any danger of seeming a bit nervous or rude!

.Back to contents-list

Speaking to the audience

℥𝄞→ Popular and jazz musicians have always (more or less) been expected to speak to their audiences, usually to introduce/welcome soloists in their band, and perhaps to say a bit about what they are performing.

This doesn't have to be at the start of the gig, of course: often it's better to get straight into the music. Then at the end of e.g. the first or second number, welcome people on: it gives your audience and your co-performers a break.

When a performer is coming on mid-gig, it's nice to welcome them as they do so, but the main thing is that they are acknowledged in some visible/audible way at some point. ←𝄞℥

ℭ𝄡→ In the past, formal classical concerts very rarely included a chance for performers to speak, but that has changed a lot over the last 50 years or so. Now, it's often expected, or requested, of classical musicians as well. ←𝄡ℭ

So, it's something we all need to be comfortable with.

Speak clearly and not too fast! It's OK to use written notes, or even read from a script if you need to, provided you project the voice well and have a good amount of eye-contact with the audience: much better to do that and be confident and fluent, than to risk memorising it if it could give a less good impression - and make you feel less comfortable. However, a verbal introduction delivered fluently from memory can create a particularly good impression.

Keep it concise (usually)!!

If your audience have written programme notes, try to avoid duplicating too much of those notes in what you say.

Usually it's best not to start speaking until your co-performers are in position, but sometimes it's OK, e.g. if there are stage-set moves between pieces which the performers are doing - your speaking can keep the audience engaged while the furniture is moved. An example might be a compèred orchestral or band concert where the percussionist moves kit around between pieces: for the audience, the concert flows better if the speech follows on from the previous applause without waiting for any resets to be completed.

Sorts of things to say when introducing a piece of music on stage:

- • Names of pieces plus composers/arrangers (always)

- • If it's a multimovement work, at least say how many movements (always): ...perhaps also summarise very briefly what they are;

- • Something about the context of composition (often useful):

- ◦ If it's an opera aria, very briefly introduce the character singing it, and where he/she, and the aria, fit into the plot

- ◦ If it was originally something else, e.g. part of a film score that became a ballad, or a ballet that became a chamber suite, or a transcription from one instrument to another, etc.

- • Summary of the meaning of any song text that isn't in English (always, unless the audience have a printed synopsis or full translation)

- • If it was written for particular performers, and how that influences the nature of the piece (if relevant)

- • When the piece was written, and any stylistic elements or character of particular interest (often, if not obvious)

- • ... other particularly salient points (maybe)?

- • If appropriate (!), some anecdote more or less related to the piece or the concert. This could be thoughtful, humourous, etc...

If you are introducing e.g. a set of songs, you have essentially three alternatives.

- • Introduce the whole set before you start the first one. That allows you to maintain an unbroken atmosphere throughout the set if you want to do that.

- • Perform the first one, then introduce it retrospectively. Then say what you're about to do, either just the next song, or all the remaining ones.

- • Precede each song with an introduction. If your audience don't have written programme notes and there is a lot they need to know about each song, this can work well.

Back to contents-list

Interludes and the "during"

- • Gaps between pieces, and gaps between movements, songs, etc., are all part of the performance! This means:

- ◦ They form part of the overall architecture of a performance, re.:

- - sound

- - what it looks like - your body language etc.

- - overall effect and mood

- - silence can be a key part of a performance, be it for surprise, or allowing the audience to take in some very intense event, etc. These moments need as much care as the notes!

- ◦ You can build in some discrete down-time, provided you make it look good - move fluently, and hold yourself well on stage:

- - If you need water on stage, have it well presented - i.e. in a glass, on a table, if possible. Pause for a second or two before going over to it, and then settle yourself when you get back to your performing spot - don't rush.

- - In many cases it's possible in a full-length concert, or even a lunchtime-length one, to successfully plan a short interlude where you go off stage for break. Don't put one in randomly, or even arithmetically, without considering whether that's a point where the recital overall could do with a breathing space.

- • Gaps within pieces/songs, are also part of the performance! They are often key parts of the rhetoric and pacing of the music. Beware:

- ◦ Composers don't always help with this!

- - For example, sometimes they might demand a change to or from muted playing: there might be a significant general pause, and not time either side of the pause to allow the change of mute. In that case, you might have to make a visual virtue of the mute change: allow the general pause to take effect - rhetorically - only then, move and start to pick up or place down the mute. Or you might want to do it more quickly and dramatically - depends on the character of the music.

- ◦ Nor do printers! Page-turns can also be pitfalls. Again, they need to be integrated into the character of the music wherever possible.

- • Applause during pieces:

- ◦ ℥𝄞→ Acknowledging applause after solos in a jazz piece is always nice: it's not usually possible to do in a very fulsome way, as often you'll still be performing as you finish your solo and move into comping or into a bridge or head. It's nice to at least smile at the audience, or nod, if you can. ←𝄞℥

- • Applause between pieces:

- ◦ Your plan for the progression of moods and character through a recital will naturally suggest where are break points, and where you think it's appropriate for the audience to applaud: ℥𝄞→ This can apply to jazz sets as well as classical ones: a segue between numbers can be very effective. ←𝄞℥

- ◦ Of course, you ultimately can't be in full control of audience reactions. But you can:

- - Signal to the audience when they can relax and applaud

- - [Sometimes, also in programme notes, both by the way you format the playlist (groups of pieces/songs etc.), and perhaps a polite note somewhere on the playlist]

- - [Indicate it in the way you describe a piece or set of pieces, either verbally or in the written programme notes, if you have either opportunity]

- ◦ Sometimes, with the best will in the world, things don't always work out as you intend: someone in the audience might break the atmosphere and applaud when you were hoping they wouldn't. Try not to be frustrated by this. And never show any annoyance to them, not even by the slightest signal in your facial expression, or even small sudden muscular tensing (that can be more visible than one realises):

- - The obvious courtesy is to give a quick smile and/or nod in their direction, to say thanks, then return immediately to your "I'm performing now" position, facial expression, etc. That way, the message is given politely and clearly.

- - It's probably acceptable to an audience for you not to acknowledge it in this situation provided you maintain absolute intensity of concentration, and of visual manifestation of that concentration, across the gap. But even then there is perhaps a danger that it could come across as a bit negative or slightly rude. If you already have a good sensitivity to the feelings/attitude etc. of that particular audience, you'll be in a better position to judge this. If you don't feel you know, it's best not to try this approach.

Back to contents-list

Ending a piece

Generally endings of pieces these should be in character. If it's a quiet ending, it's usually best to hold the moment, i.e. don't move for a few seconds until after the final note has died away. This might seem an eternity to you, but it won't to the audience. You should aim to vary this, as you don't want the same amount of intensity/drama for each piece.

Don't be afraid of silence!

A bravura ending can of course be quite different, with a definitive, perhaps even a bit flamboyant (but not pretentious!) gesture which clearly signals to the audience to do what they will doubtless want to do, i.e. applaud straight away.

In either case, if there is accompaniment which continues after you've finished your final phrase, or in any interludes in pieces for that matter, you can relax to a certain extent mentally and perhaps physically so long as no hint of disengagement is discernable to the audience. Any intentional CDG_list_item_within_main_content ("Applause between pieces:"); relaxation in the musical intention during this time must be that, and can be signalled in your body language, but you must never look like you're switching off. You should always be, and look, involved with what your co-performers are doing.

Think about and plan:

- - How much gap do you want between movements or songs?

- - What is your physical movement/stasis before and after the ending?

...then practice this lots of times - it's one of the bits of the performance we tend to neglect in our preparations.

.Back to contents-list

Leaving the stage

Again, there are some examples further on. In general:

Once you've acknowledged the final applause, go offstage. Remember which direction to head off in! It's best if you do as little else as possible, in terms of collecting music, stands, etc. Though of course if you have an instrument you would normally have carried on to the stage, do take it off with you. Sometimes, though, it is necessary to take other stuff with you as you leave.

Keep smiling and looking relaxed...

If the applause keeps going after you get off stage, provided the promoter

hasn't told you not to, by all means go back on stage on to acknowledge it.

But don't hang about unless the audience really are in raptures...

.

Back to contents-list

Moving around the stage - some examples of routes, positions, etc.

Here are a few examples of good and not-so-good things to do in some typical stage setups. (More will be added if people feel that's useful). These are not presented as ideal or best solutions to any situation: so long as you understand where they come from, and the effects of what you are doing, you should feel free to come up with your own equally good, or better, ways of doing things!

Also, These diagrams also are no more than examples: virtually any feature of them could be varied - in different positions - or absent altogether (e.g. music stand, water, mute-stand, etc. etc.). Other things might be present which aren't shown here. These are not in any sense a comprehensive set of instructions! But I hope they are enough for you to see what's going on and plan your own setups effectively: ones that suit you and the audience really well.

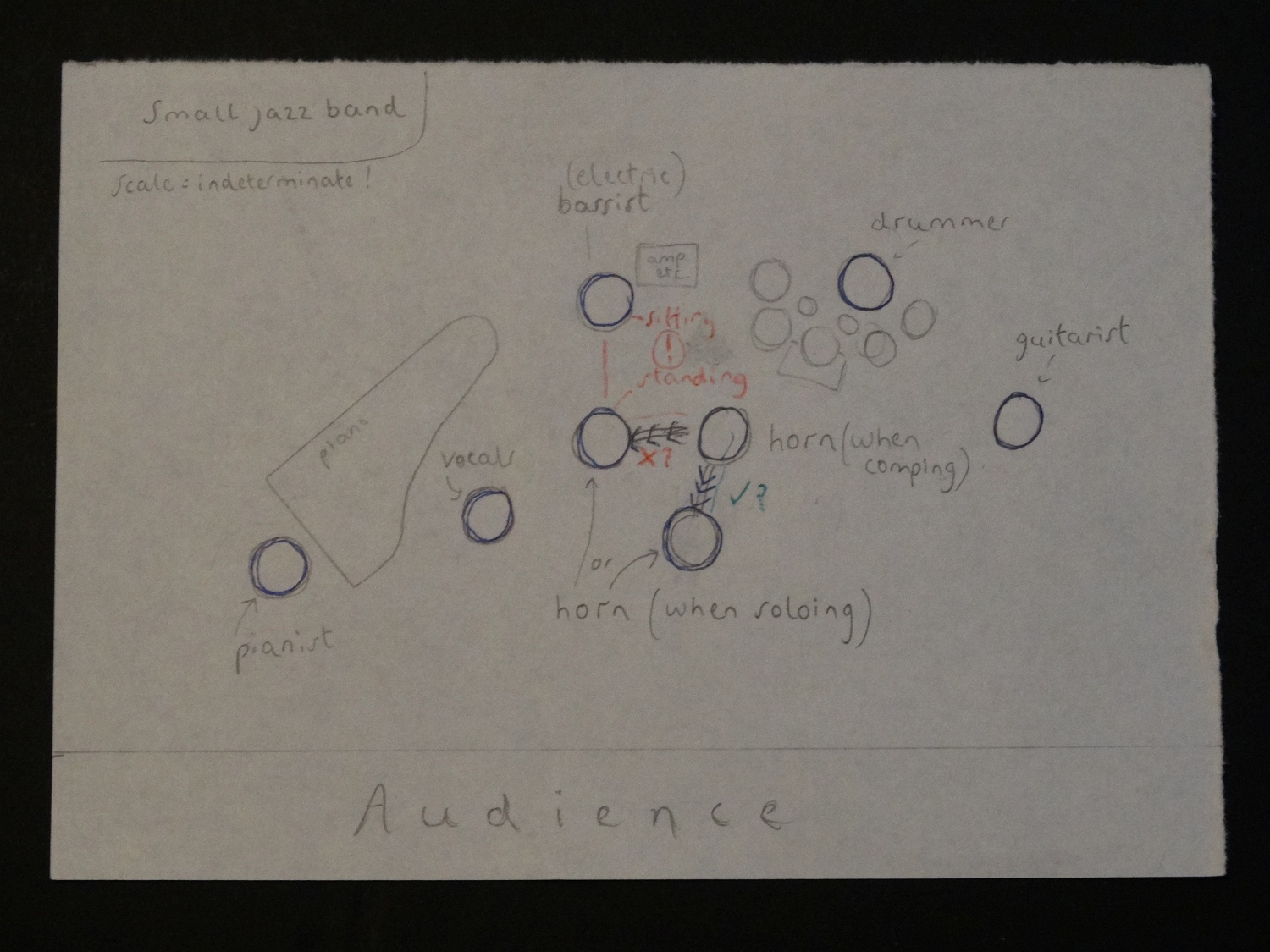

Small jazz combo:

℥𝄞→ When a stage is not very wide, one can end up with a setup where the bassist, or other rhythm section players, are in the middle and can easily be blocked more starkly than you intend. This is particularly so if they're playing electric bass sitting down, and indeed for the kit player who'll also be sitting (usually!).

Of course it's perfectly appropriate for a horn player or lead vocals to step into a more prominent position for a solo, then back again when you return to band work, but it looks better if you go forwards a bit, not just across to the centre, if by doing so you stand close to, and bang in front of, the bassist! ←𝄞℥

℥𝄞→ By the way, if you have a small group setup and think it would be nice to keep the piano sound natural (unmiked), be careful with this sort of position. A lot of the sound with a grand piano reflects off the lid, i.e. in a direction perpendicular and to the right of the pianist: that's often just where the horn sections and/or vocalists are standing. In a cramped stage, this can weaken the piano sound to the point where it might get out of balance with the kit, and if you're not careful, with the bass and guitar amps. ←𝄞℥

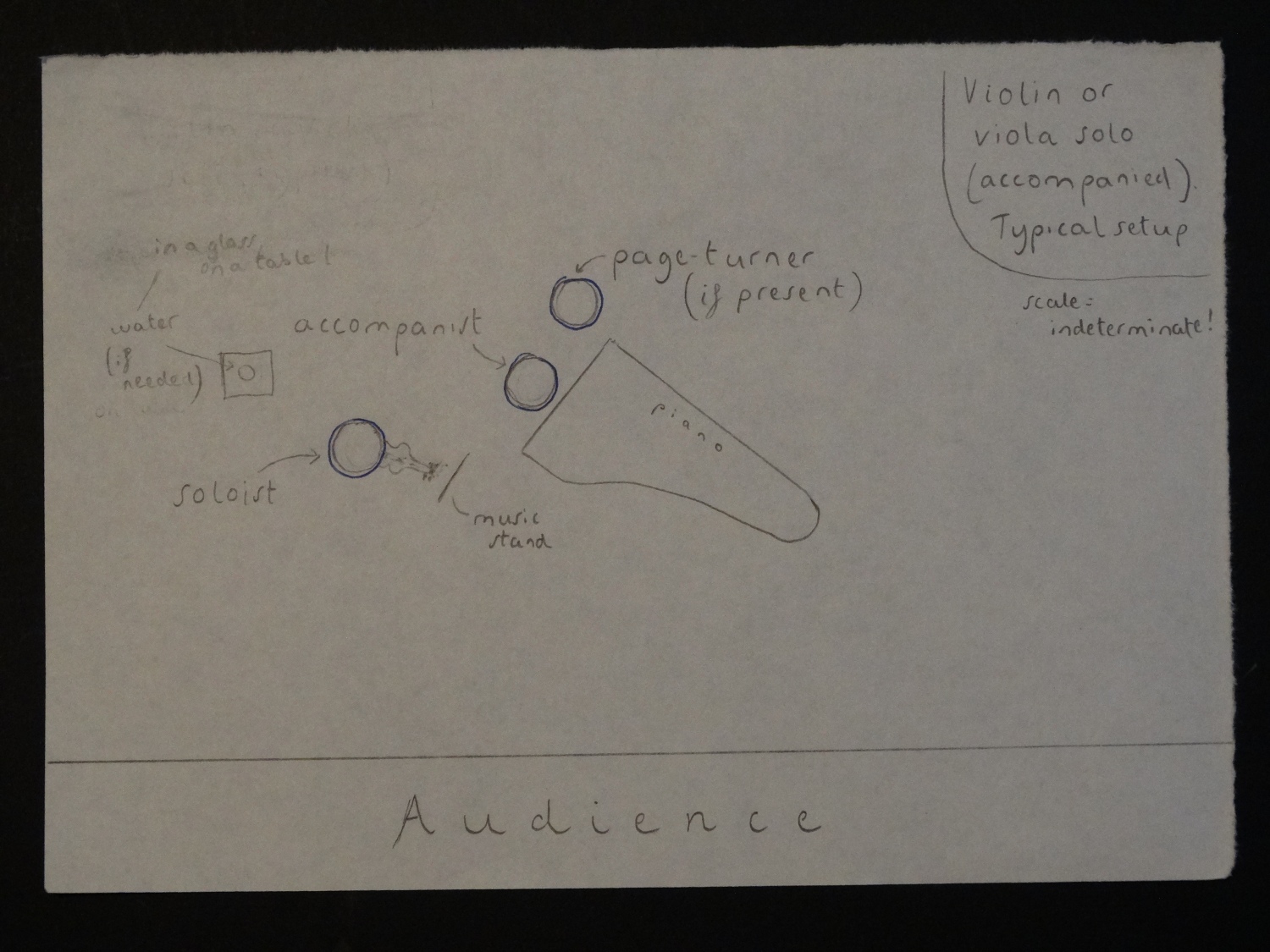

Soloist with piano (usually, but not only classical) - typical setup for most instruments and voices:

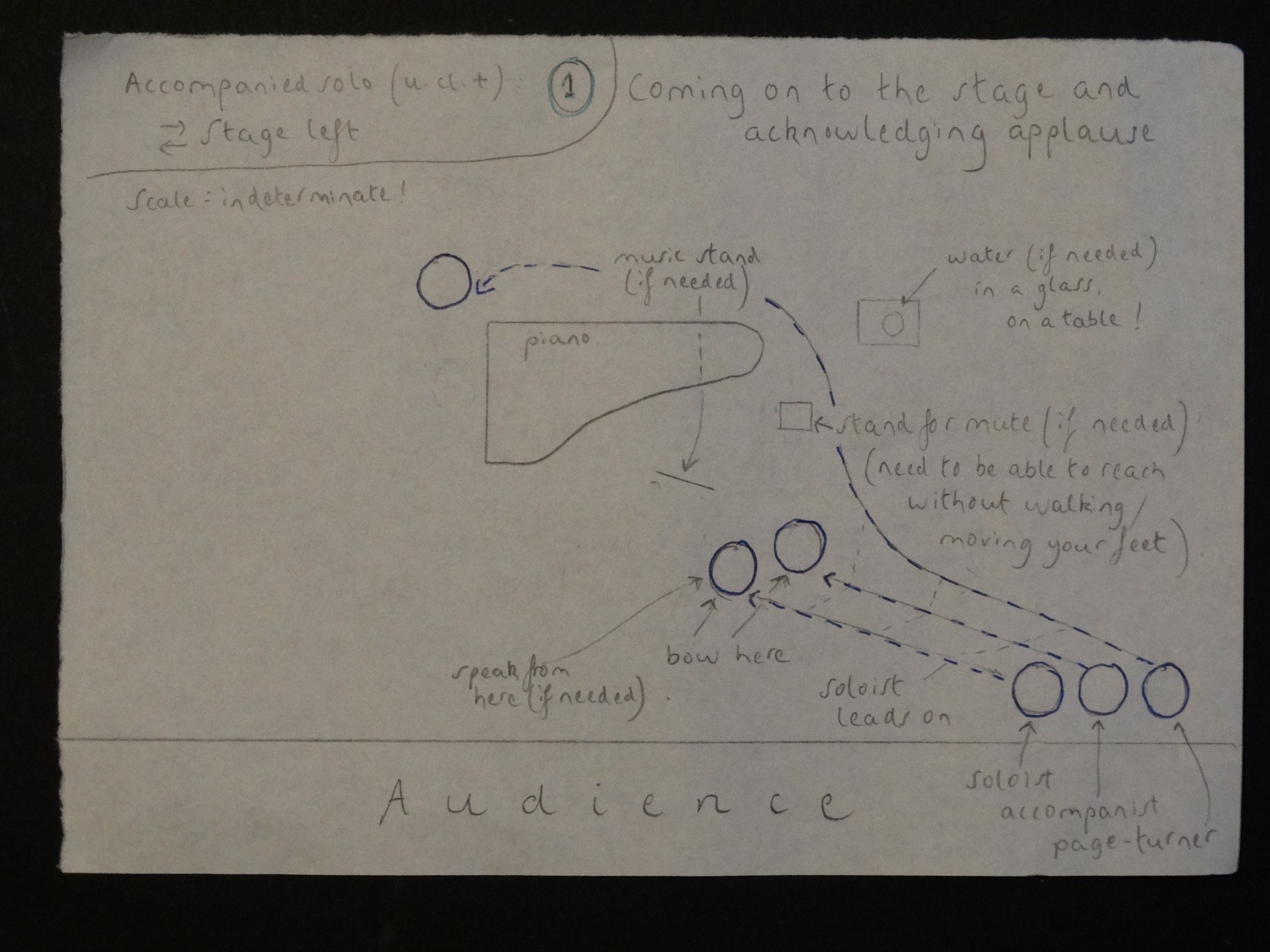

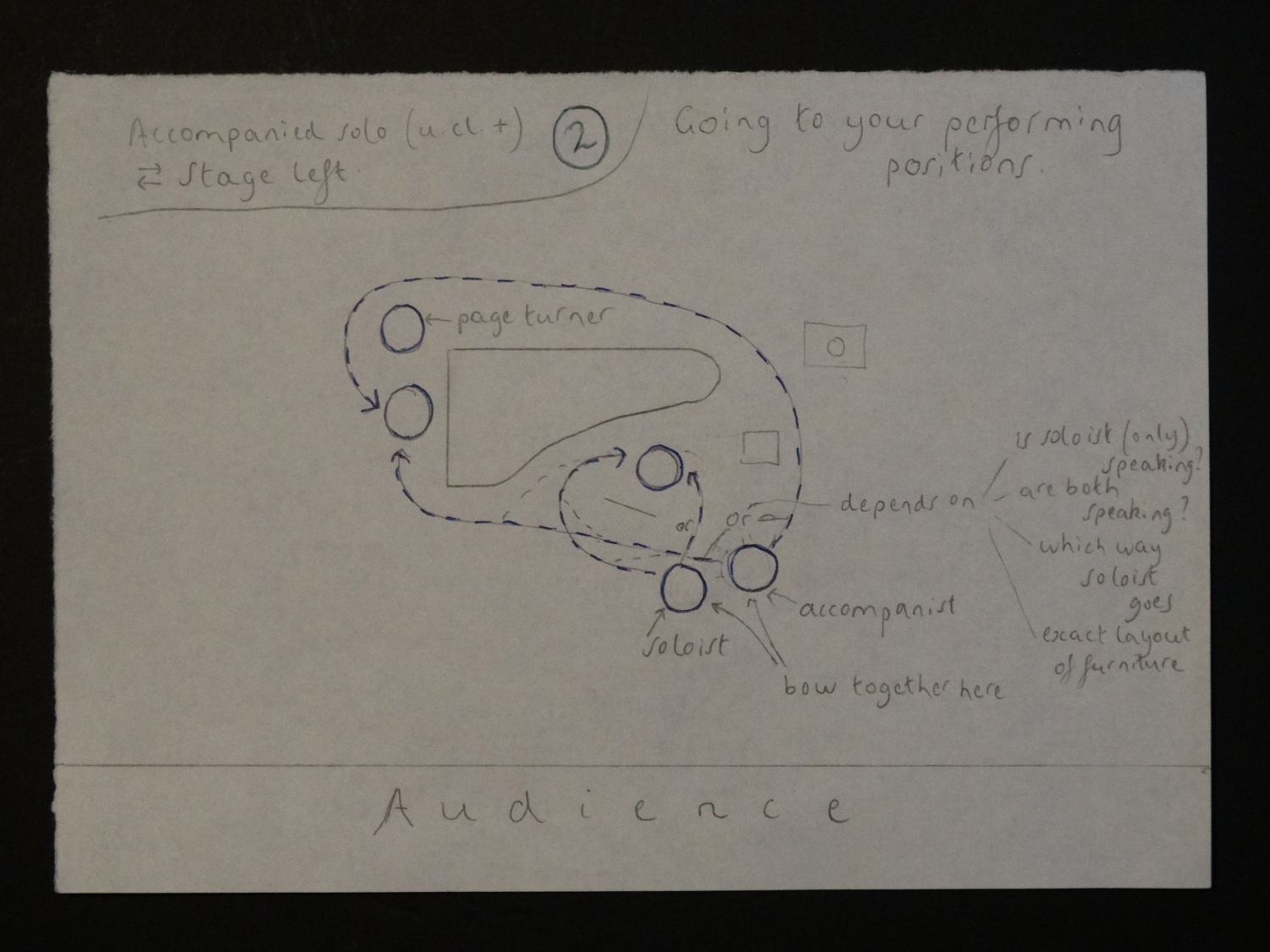

A very common position for the piano when accompanying a soloist (apart from violin and viola) is shown in these diagrams. Of course it doesn't have to be like this, but it's a good fallback and is what is done most often. It allows the piano lid to reflect directly to the audience (or not, as you choose), and allows the pianist to see the soloist well without compromising the soloists flexibility with both sound and visual communication for the audience.

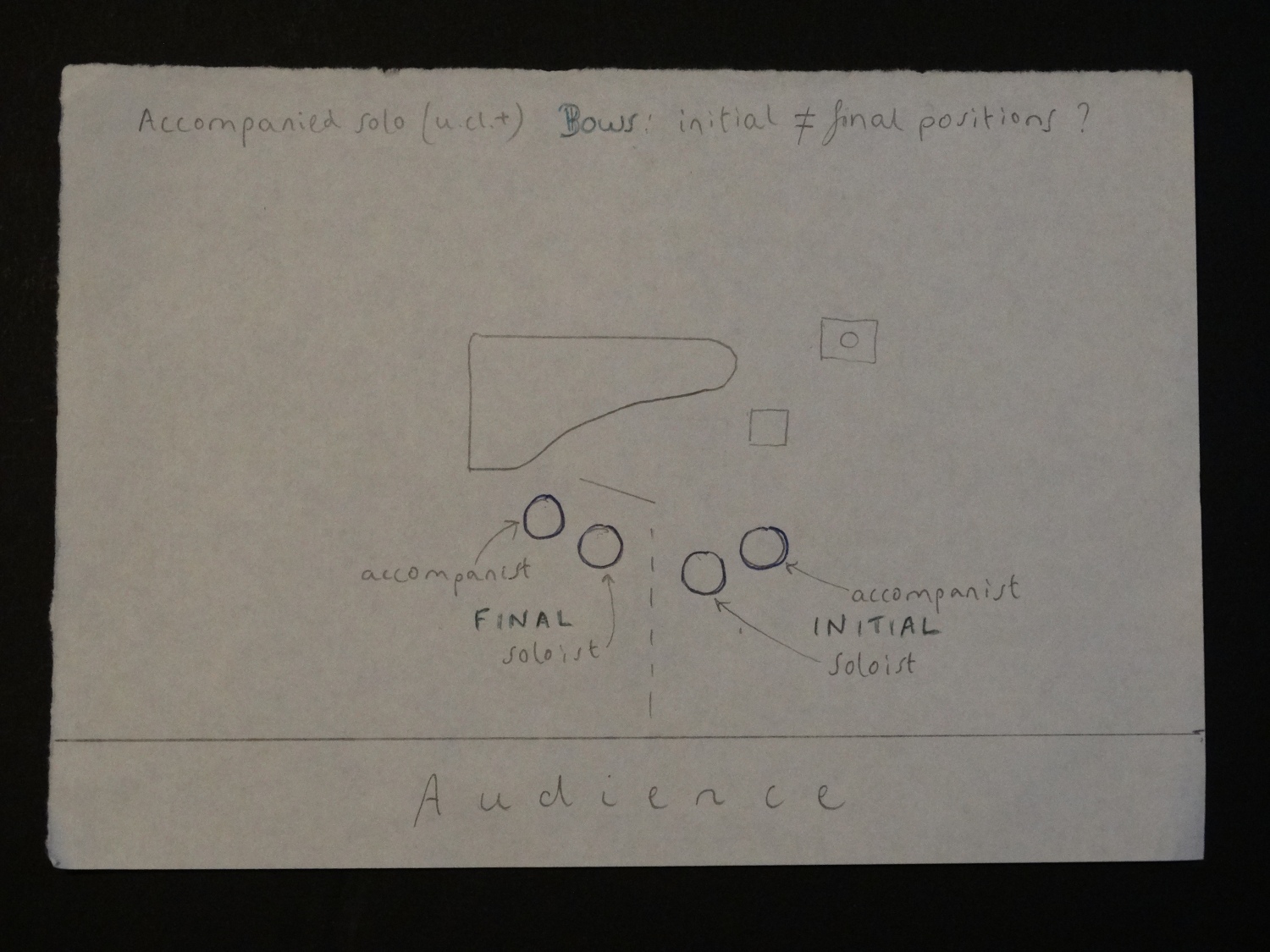

These examples are for entrance/exits which are stage-left (i.e. what is the left-hand side of the stage, once you are facing the audience), as it takes a bit more thought than the stage-right equivalent. Hopefully these examples will allow you to see why, and to see what to do in a different setup (and entrance/exit stage right).

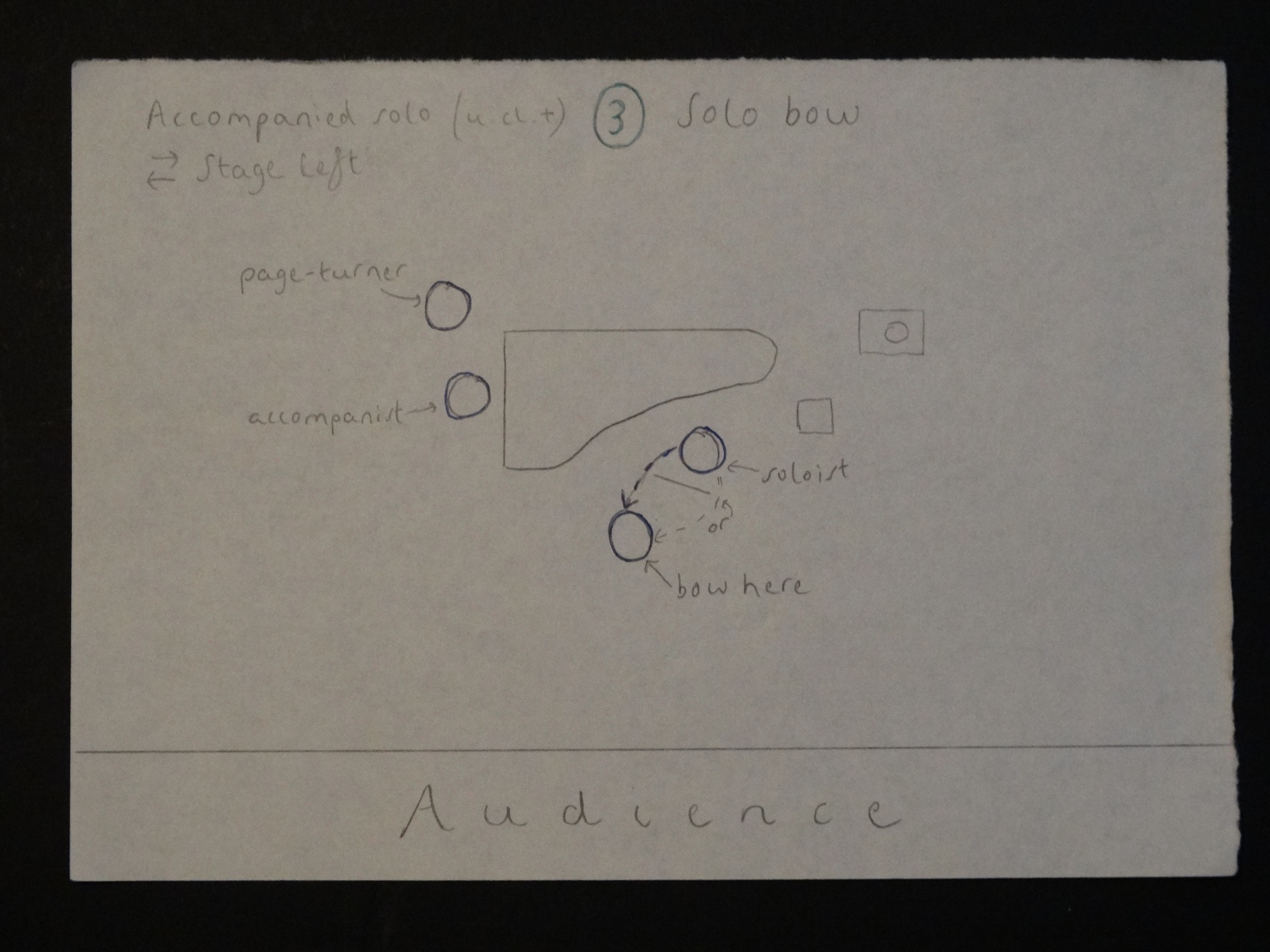

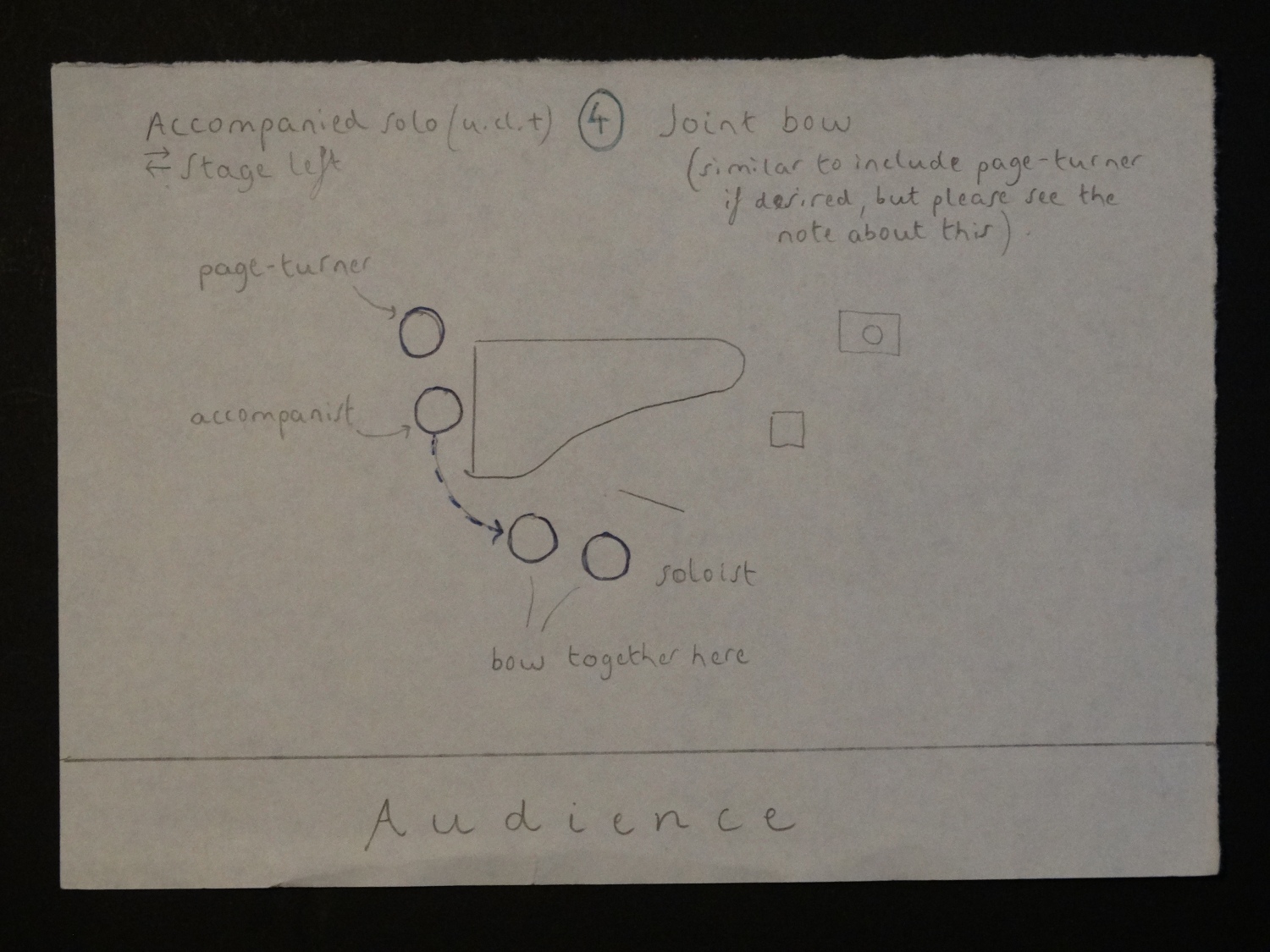

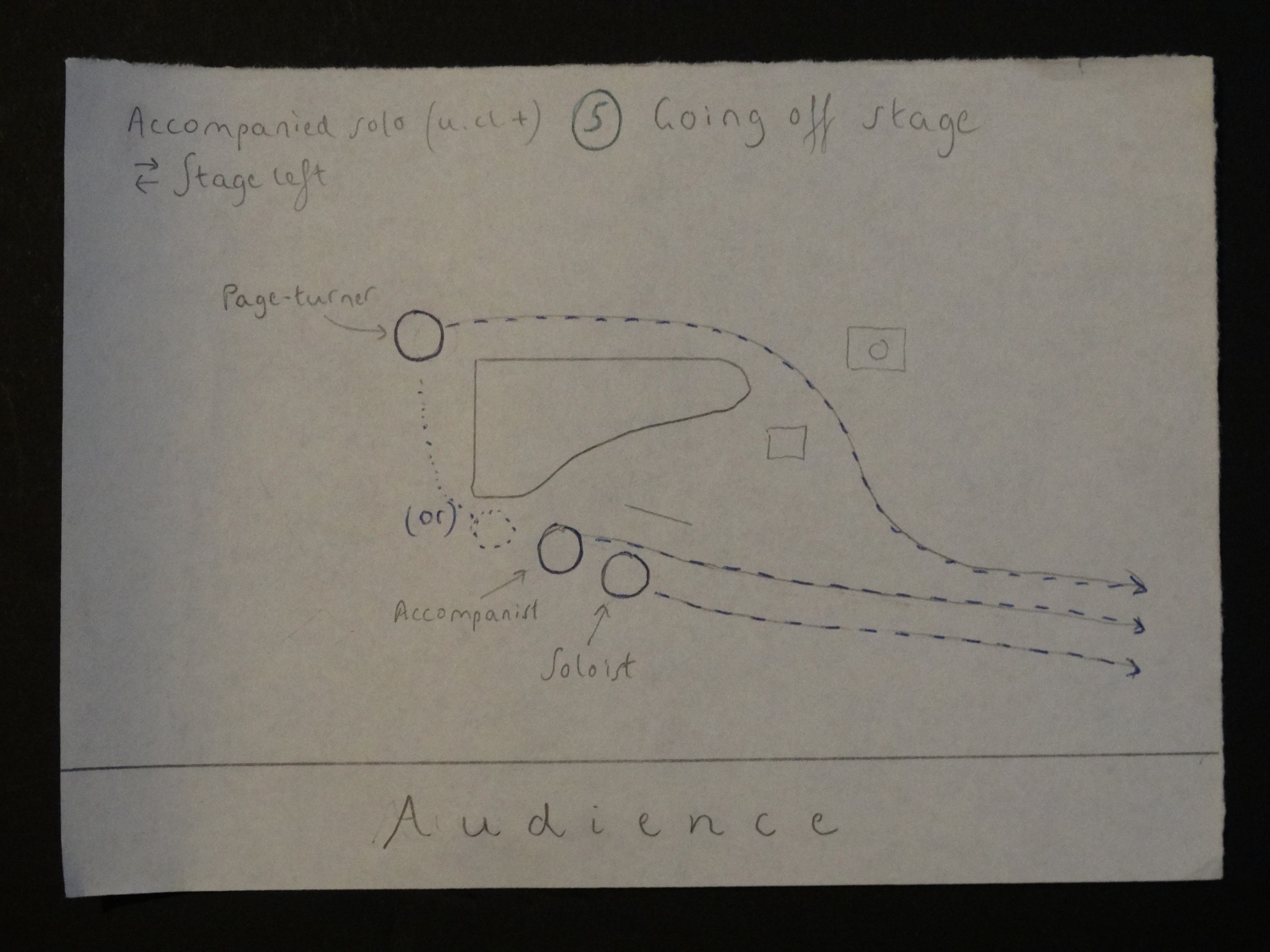

If you're coming on from stage left you might not want to bow at the start from the same point on stage as you do at the end! These diagrams have suggestions for how you, the accompanist, and a page turner, might move around the stage. These are of course only suggestions. They assume that you will take a bow on your own first, then (with a smile and a gesture) invite the accompanist to join you for a second bow. They also assume that the accompanist will wish, when joining you for a bow, to stand a little further back on stage with you. But people vary on this, of course.

They also assume that the page-turner won't bow! You might well want to acknowledge the page-turner - they are doing a vital, surprisingly tricky, and much under-appreciated job, after all. (As accompanist, I always at least turn quickly to the turner and say thanks, before I get off the piano stool - it's the least one can do!). So, a noble sentiment, for sure. However, bear in mind that many page-turners might feel uncomfortable with this, and prefer to remain in the background. Whatever their own feelings about their role, the sheer unconventionality of being brought into the limelight might feel a bit odd. (I also speak as someone who has often done that job...). So don't spring anything on them!

So here is a typical sequence. Again, please feel free to change it, so long as you understand what you're doing!

Finally for this setup, just a quick comparison of positions for acknowledging initial vs. final applause:

Viola or violin soloist with piano: typical setup:

Again, this is only one way of doing things, but try to see why: How does a stringed instrument like violin or viola project the sound? Where is the sound-board, and the "f-holes"? And how does a player usually tilt the instrument? What's best for projecting the sound to the audience?